Hello and welcome to the Dr Duckie blog!

I'm doing a PhD about Duckie's work and whether having fun can make the world a better place. Although I’m expecting the main focus of my research to be on what might be called Duckie’s social-outreach projects (The Posh Club, The Slaughterhouse Club, D.H.S.S. and so on), Duckie in Sitges – a week-long trip to Spain the company organised for its punters from 19 to 26 September 2014 – was a great chance to spend time with the company’s hardcore devotees. After all, there’s a good chance anyone willing to devote a good chunk of cash and a week or so of their time to a holiday organised by a nightlife company is a true believer.

Tim Brunsden's video about the Duckie in Sitges experience

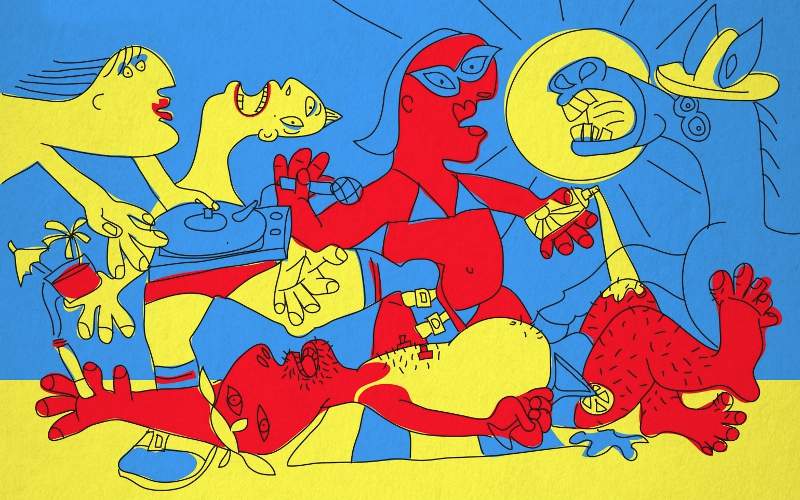

The event started before anyone reached the airport thanks to Duckie’s characteristically sophisticated publicity material. A good-quality small-scale 24-page colour programme detailing the week’s programme was circulating months in advance, combining references to high and low culture in typically Duckie style while reinforcing the company’s brand. The cover evoked Orwell and Picasso, describing the event as a “Homage to Catalonia” and illustrating it with a brilliant burlesque of Guernica, featuring caricatures of Duckie’s core members indulging in cocktails and sunburn, and a Spanish beach donkey in place of Picasso’s agonised horse.

The destination came with its own set of associations. I’d never been to Sitges before but knew that, along with Mykanos in Greece, it was Europe’s most gay-friendly and hedonistic package-holiday destination. I was able to get a better picture at the welcome drinks organised for the Friday night and the Duckie club night held in a pretty theatre on the Saturday. I spoke to two people (separately, not friends or partners) who had been Duckie regulars for more than a decade but were also regular visitors to Sitges – a woman with seven previous trips under her belt and a man with 10. Both agreed Duckie and Sitges were a good match: they already saw a few of the same faces at the club in London and the resort in Spain but thought a Duckie event might tempt people who wouldn’t otherwise give Sitges a go, while the Sitges scene would benefit from events and entertainment with a bit more imagination and bite.

As the man put it, Sitges regulars are “older, more discerning, like to dance but also like a good restaurant, beach, good music – we don’t want to take our tops off and dance to house music and take all kinds of drugs but we aren't ready to die yet!”

The venture succeeded in attracting a cohesive contingent – the Saturday club night attracted about 300 people, including non-Duckie holidaymakers, locals and some travelling down from Barcelona; the company estimateS that around 250 people made it out from London for at least part of the holiday. On a highly unscientific survey, I’d say the average age was closer to 40 than 30 or 20, a large majority of faces were white, and there were perhaps twice as many men as women.

The venture succeeded in attracting a cohesive contingent – the Saturday club night attracted about 300 people, including non-Duckie holidaymakers, locals and some travelling down from Barcelona; the company estimateS that around 250 people made it out from London for at least part of the holiday. On a highly unscientific survey, I’d say the average age was closer to 40 than 30 or 20, a large majority of faces were white, and there were perhaps twice as many men as women.

There was a palpable sense of familiarity and shared sensibility and a general friendliness, perhaps enhanced by that little frisson you get when spotting a familiar face in unfamiliar surroundings, even if you’ve never spoken before. The feeling was one of a moveable microcommunity, somewhere between a travelling circus and a religious order. Naturally, there was an economic threshold to participation – the cost of the holiday and the ability to take a week off work (although it was possible to pop over for the weekend). On stage on Saturday night, hostess Amy Lamé observed conspiratorially that “we’re just that little bit posh now, aren’t we, now that we’re over 40? Paying a bit more for that [holiday] flat…”

In terms of performers across the week, most were familiar from the London scene – though their turns tended to emphasise the physical and visual rather than the verbal, apparently to help make work accessible to non-English-speakers. But there was some local talent, including La Terremoto, a singer who achieved online notoriety for a version of Madonna’s Hung Up that seemed to be based in cloth-eared mistranslation. Loli’s performance was always cleverer than that, and it was a treat to watch her on Saturday night roundly seeing off any preconceptions about the naïve/stupid foreigner with her assured control of her performance and the crowd.

It wasn’t just about the performance. There was plenty of time for sunbathing at the beach and exploring the picturesque old town under one’s own steam, along with a Duckie-organised tapas tour, bar crawl and other social activities. These organised events were pretty casual – there was generally only one a day and certainly no kind of register was taken, so holidaymakers were able to dip in and out. Overall they were an opportunity to mingle and bond as a group, though they also offered the opportunity for more or less unambiguous instances of exclusion, with groups forming (or already present) within the larger Duckie-in-Sitges group that were not always welcoming of others. There were moments – some gossip here, a blanking there – that were redolent of the petty manoeuvrings of a school trip.

On Monday, ex-pat Brandon Jones delivered what was indeed an interesting talk about local Catalan customs of the kind that would be on display during Tuesday’s Santa Tecla festival. Jones’s talk was liberally illustrated with his own video reports, and his account of how Catalan culture had been repressed under Franco but emerged resurgent under more liberal subsequent regimes made me wonder whether it could be compared to queer culture in certain ways. Most striking in the description of fiesta customs were the ‘human towers’ – huge communal acrobatic endeavours in which dozens or even hundreds of people work together to raise one another on each other’s shoulders to create intricate structures that can reach storeys high – and the copious amounts of fireworks let off in the streets as hundreds of revelers mill about. As Duckie producer Simon Casson noted, “it’s very exciting but very unbritish.”

We got to experience both towers and fireworks first hand. On Monday night, the Santa Tecla festival kicked off with a truly spectacular municipal fireworks display above the beautiful church that stood a couple of stone stairways above the beach. It was easily the rival of any new year display on the Thames, concluding in a volley of blinding flashes and deafening bangs.

Sitges was a site of performance long before Duckie’s arrival, both in terms of traditional parades and gay nightlife. During our introductory tour, we passed through a small square flanked by gay bars whose outside tables were arranged so that all chairs faced into the square, making a de facto stage of the street and performers of all who used it. And one night, we watched Ria Jones, a British musical theatre performer doing an enjoyable cabaret show at El Piano, a bar owned by gay expats. (This wasn’t a Duckie event.) Her set – first half showtunes, second half gay anthems – felt formulaic, even calculated to me but she had a great voice and an easy way with the crowd, and her material was affirming through performance a certain kind of gay identity.

But the most moving instance of performance I saw all week came early on the afternoon of the Santa Tecla fiesta, before the parade and the fireworks. This was the human tower. By the standards of the towers seen on Brandon Jones’s video, this was modest but still spectacular: a child on the shoulders of a woman on the shoulders of a man on the shoulders of a massed huddle of dozens of supporting participants, collectively working their way down the flights of stone steps from the church to the seafront.

The acrobatic skill of the display was impressive enough – the almost-blank looks on the faces of the trio in the tower itself betraying the occasional glance that might have been concentration, might have been zen-like calm, might have been sheer terror. (There have been human-tower-related fatalities before.) But what was truly affecting with the knowledge that these weren’t professionals but motivated residents, joining in a performance that honours and affirms community and cooperation yet embraces fragility and temporality rather than asserting force and permanence.

In Catalan, Jones told us in his talk, ‘fent pinya’ literally means ‘to make the base of a human tower’ but colloquially means ‘to work together’. It seemed to me that Duckie in Sitges was, in its less disciplined, less spectacular way, something of a human tower in itself, a group endeavour willed into existence by people expressing their fellow feeling, their membership of a tribe.